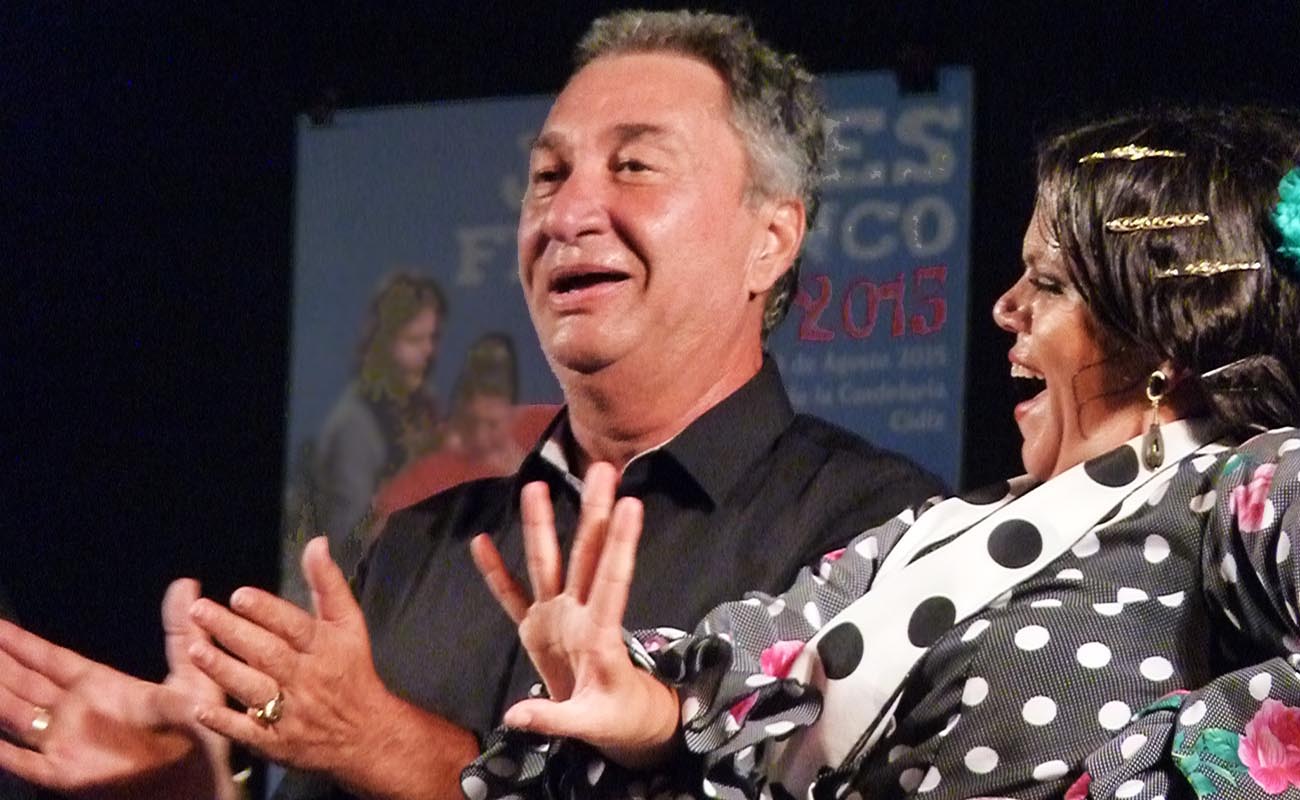

El Purili of La Línea

I haven’t seen him performing live yet, but I’ll do it soon. Some time ago I watched him sing and dance in a video and I was taken aback. I couldn’t believe that a young kid could have so much art and look so much older when getting up and dancing a little por bulerías. I would assume that he would

I haven’t seen him performing live yet, but I’ll do it soon. Some time ago I watched him sing and dance in a video and I was taken aback. I couldn’t believe that a young kid could have so much art and look so much older when getting up and dancing a little por bulerías. I would assume that he would be a fan of Camarón or Morente and be full of ojana, yet he is a fan of Perico El Pañero and when he sings he recalls the lives of his ancestors with his cante gitano (or rather “cante gitano-andaluz”, like Antonio Mairena would say). This is obviously a miracle in our days, when the youngsters are often so distracted. I don’t mean to criticize those who try to emulate Morente or Camarón, as I myself looked up to them, too, and not just regarding their singing style, but the way they felt and experienced cante. I say this on account of those who are still wary of flamenco because they feel is a thing of their grandparents, anachronistic and kind of old. I like Alonso Núñez, El Purili, precisely for that reason: because he has learned from his elders and from meeting other people outside of his family in gatherings of flamenco experts (the so-called cabales).

This kid from La Línea de la Concepción has a style of singing and dancing that reminds me of the likes of Anzonini, Paco Valdepeñas, Miguel Funi or Antonio Mairena (the cantaor from Mairena was a superb bailaor). There have been many others like them, but not a lot, much less young like El Purili. We must be fair and mention artists from Seville like Luis Peña and Javier Heredia, who for years have been practising and preserving this school, with few people caring, that’s the truth. Perhaps it’s Perico El Pañero, from Algeciras, who is spreading that way of doing flamenco. And his brother José, too. They’re both artists of great purity, meaning authenticity and sincerity, not an absence of blending. I’m old enough to know very well what purity in cante means.

El Purili is still a teenager and we don’t really know which paths he’ll chose in the future, but I believe he won’t stray much from his current path, because we can see in his face, when he sings and dances, that this is the way he likes and feels. It’s truly worth watching the video where El Pañero sings and El Purili comes out to meet him, as in a trance, drunk with the art of his mentor. That’s why I don’t think he’ll ever lose this magic, because that’s what he truly cares about. I talked to him yesterday to write this article and I was amazed at how well he understands flamenco in general and cante gitano in particular. He’s 17 years old but has the maturity of a 50-year-old, possessing wisdom uncommon in a teenager. Perhaps that’s because he was born in a family of flamencos, although not all perform on stages. Rubio de Pruna is a first cousin of his father, and, according to himself, his great-grandfather was a superb cantaor, although he never performed on a stage.

When I hear this kid talking and then see those artists giving ojanato make money, I get in a bad mood and curse. Flamenco, the kind of flamenco Purili does, is a legacy that has to be taken care of. Anyone can sing as they feel like, to the best of their abilities, but it’s unacceptable to barter away or damage that legacy, a treasure that we have in Andalusia which we sometimes fail to appreciate, unaware of its importance.

I’m not saying this just on account of this kid from La Línea, but also for those who try to sing a malagueña de Chacón and ruin it, even forgetting the lyrics. A malagueña de Chacón is also an important legacy, although a certain writer of Jerez would not regard Chacón as a cantaor, but merely as a “singer” (“coplero”).

El Purili is a treasure of our days, and those of us who have the responsibility of looking after the arte jondomust pay attention to him, accordingly. Not for him to make money with our help (although there’s nothing wrong with that), but so that other young artists follow in his footsteps.

Translated by P. Young