Tales and fables of cante

Why is that Joaquín became so renowned in flamenco history, then? Because he personalized his cante in a brilliant way, because he was a well-known and well-liked character of Alcalá, and because he represented the authentic cante of that land, the soleá

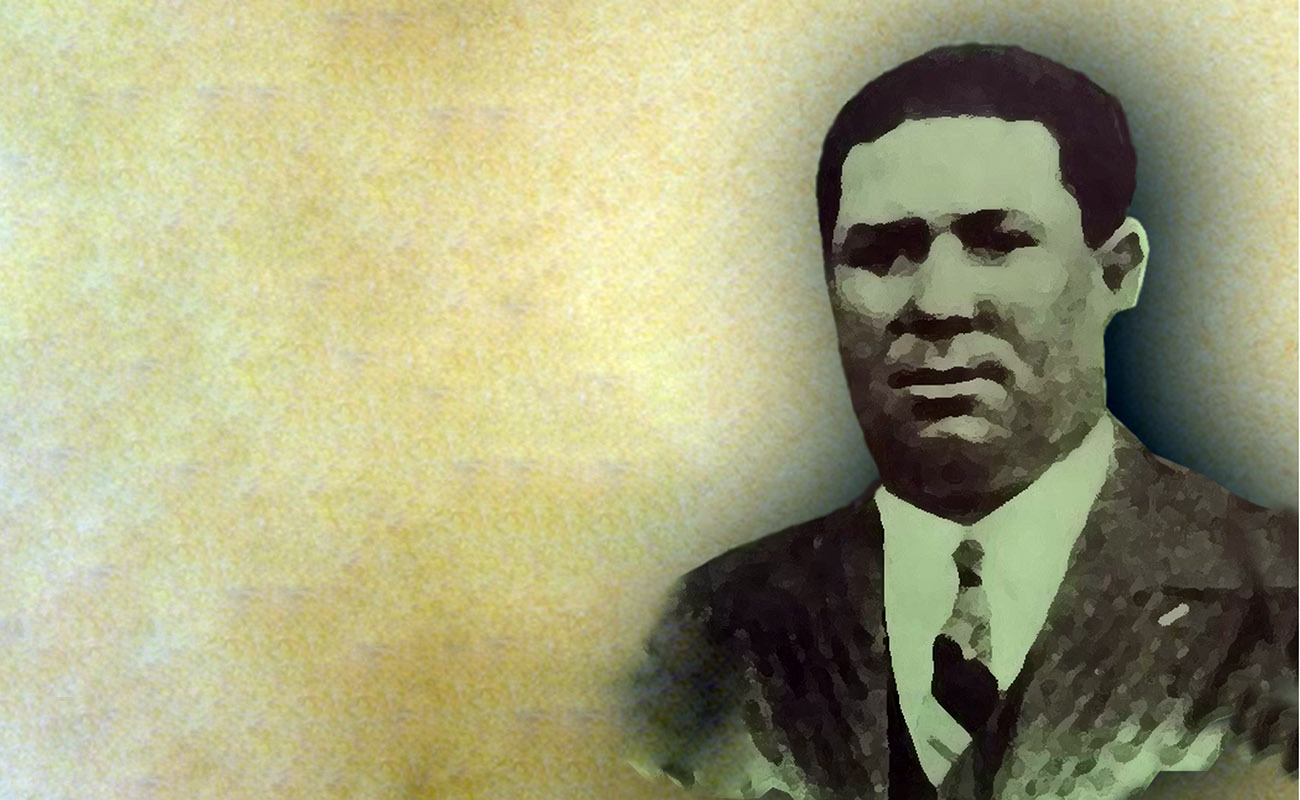

Those of us who pride ourselves in knowing flamenco history in depth know that there are artists who have been elevated where they don’t belong. It’s tricky to give examples because, even as they’re no longer with us, they still have living family and fans. This is a topic that has never been discussed as it should, in order to correct injustices and straighten up the record. We could mention, for example, the celebrated Joaquín el de la Paula (Alcalá de Guadaíra, 1875-1933), the so-called king of the Alcalá soleares, although he never recorded his cante, so we’ll never know how he sang, just like we don’t know how Silverio or El Nitri sang.

Joaquín Fernández Franco, his actual name, was lionized by Antonio Mairena, who claimed to be his disciple. Before Mairena’s extolling, no one had paid much attention to that Gypsy singer from the caves of the Arab castle, who mostly performed in private parties and, occasionally, in obscure cafes and halls. People often speak about the soleares of Joaquín, in plural, while he only sang one single style, according to his own son, Enriquillo, who also used to sing in private parties. Antonio el Sevillano also told me in his own house that Joaquín only sang in one single style, who Antonio himself recorded as Soleares de Alcalá. Thus, if he only sang in private parties and never recorded anything, how come he is so renowned?

«Alcalá greatly honored him, something that didn’t happen to José Ordóñez ‘Juraco’, an earlier cantaor, or with Bernardo el de los Lobitos, who is without any doubt the best cantaor born in that land with so much flamenco tradition»

Forty years ago, I started to compile information about Joaquín el de la Paula and I went several times to the caves of the Alcalá castle, where this cantaor lived. I talked to members of his family and I even greeted one day his daughter Hiniesta, who is no longer with us. When I learned that González el Negro, his guitarist, was still alive and sold lottery tickets on Sierpes Street in Seville, I sought him so he could tell me how Joaquín sang. He told me that he was often out of tune and when he accompanied him on the guitar he had to whisper his name discreetly — Joaquínnnnnn — so he would get back in tune. He never said that Paula was a great singer, although he admitted that his style of singing, in a lower voice and not perfectly tuned, was nice and well-liked by a minority of aficionados.

Antonio Mairena talked about him with veneration and he mastered Alcalás cante like few before him. Mairena once told me at his house: “Joaquín was sweet, he sang soleás in a way that no one has ever emulated. He had a soft voice, but he embellished it nicely and I liked his way of setting the lyrics”. He never said that his cante was “homemade”, an expression he often used when he talked about de Juan Talega, Perrate or Fernanda de Utrera. he never referred to him as a “sweet hoarse”, like he did about Juan Talega. He just exalted Joaquín because he was his master, his reference.

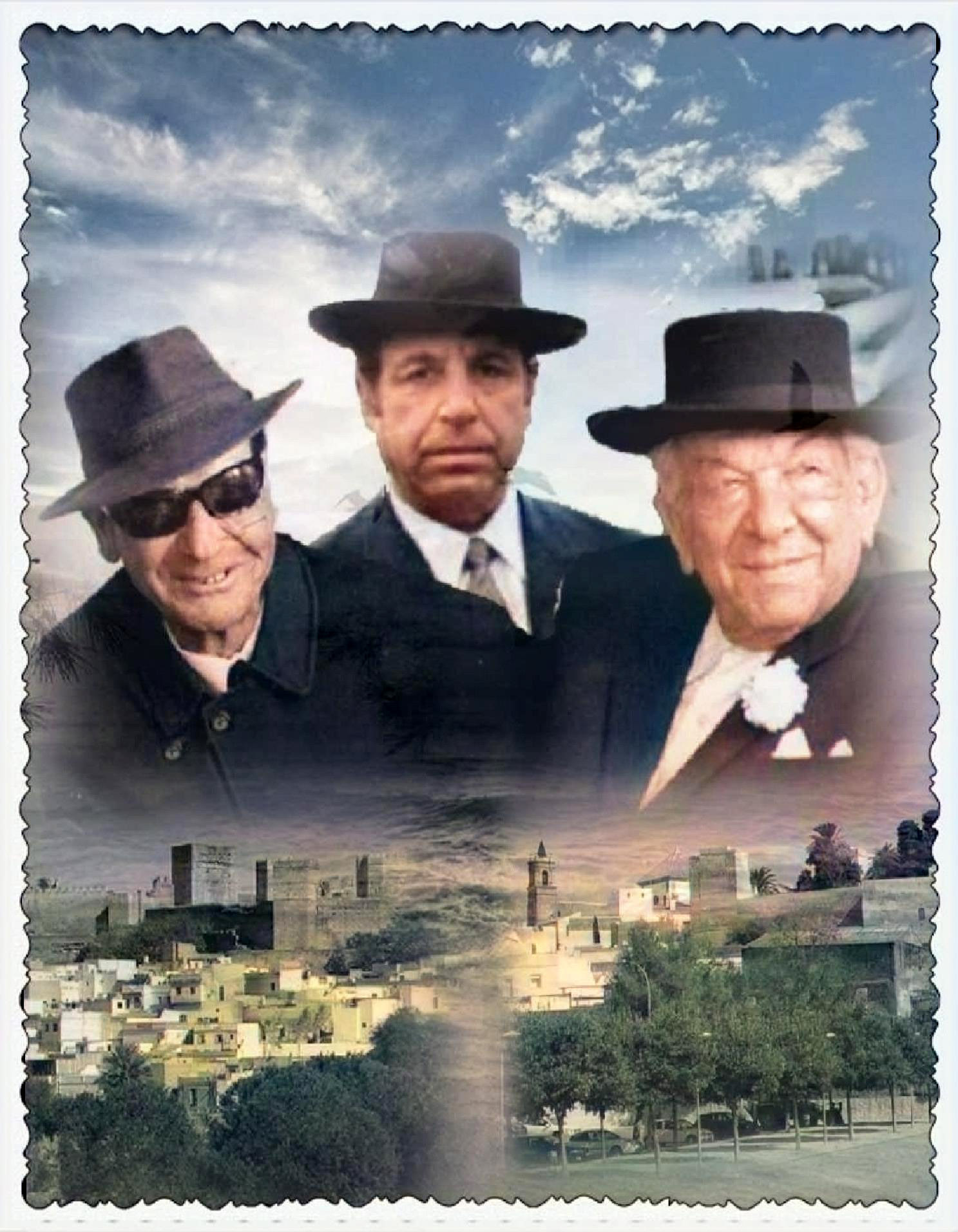

According to Enriquillo el de la Paula, son of the artist, the one who better sang his father’s soleá was Perrate de Utrera, a Gypsy with an incomparable voice. Antonio Mairena sang it in his own way, like all he sang, with a strength that Joaquín never had. Among his family, the cantaores who sang like him the most were Juan Talega and Manolito el de María, his nephews and his son Enrique.

Why is that Joaquín became so renowned in flamenco history, then? Because he personalized his cante in a brilliant way, because he was a well-known and well-liked character of Alcalá, and because he represented the authentic cante of that land, the soleá. Alcalá greatly honored him, something that didn’t happen to José Ordóñez Juraco, an earlier cantaor, or with Bernardo el de los Lobitos, who is without any doubt the best cantaor born in that land with so much flamenco tradition.

Manolito el de la María, Antonio Mairena y Juan Talega. Montaje de Segundo Jiménez Ortega.