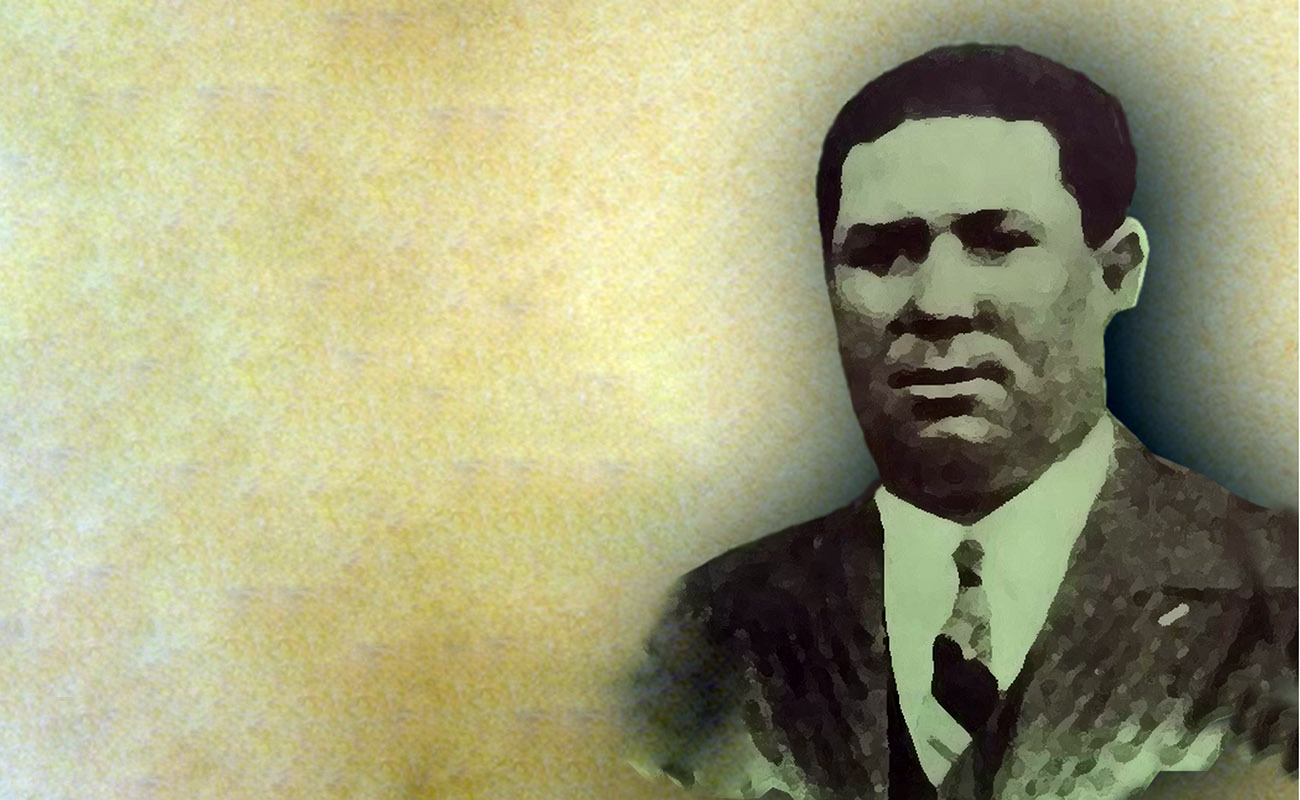

That great master from Triana

Is Naranjo recognized today as one of the great cantaores of Seville? I don’t think so. Certainly those with a solid knowledge of flamenco appreciate the style and the works of the master from Triana.

We flamenco critics have our favourites, whether we like to admit it or not. When I’m at home, I usually listen to what I really like, sometimes as part of a research, to check my conclusions, other times just for the sake of enjoying a good cantaor or cantaora. I pick an artist according to my changing moods, and yesterday I decided to review the great discography of one of the masters of cante flamenco, José Sánchez Bernal, the unforgettable Naranjito de Triana (Seville, 1933-2002), a good friend of mine and someone I’ve admired to this day. That is actually something that has given me many headaches, because, oddly, there were critics and influential aficionados who couldn’t understand my admiration for him, even in Triana, where this master of cante was born, on the popular Fabié street to be precise, the same birthplace of Curro Fernández and Diego Camacho El Boquerón, among other flamencos of that district of Seville. Fabié street is the first street on the right, walking down along Pureza street (the old Larga street) from Plaza Altozano. Naranjito’s cante style was typical of Triana, naturally. He lived for many years outside that district, though, because, among other reasons, he just felt like it. I visited him many times in his beautiful house, in the Santa Cruz neighborhood, where he had a luthier workshop, and we always ended up talking about Triana, about Manolín el de la Murga, Emilio Abadía, El Sordillo or El Titi, artists he took as role models for his career in cante, without forgetting his admiration for other legends such as Antonio Chacón, Manuel Vallejo, Niña de los Peines and her brother Tomás.

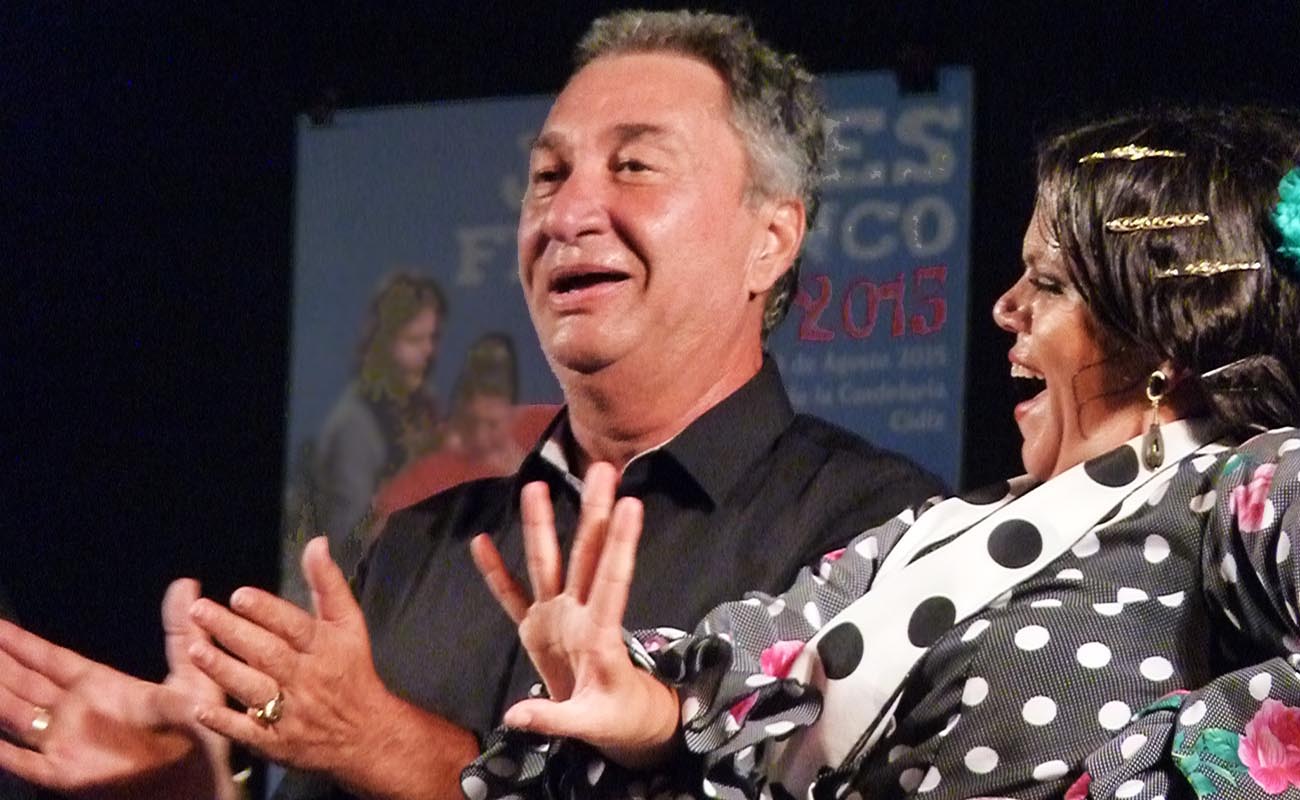

Talking about cante with Naranjo (1) was like talking to an expert flamencologist, because he knew about flamenco perhaps more than anyone else, and not just about cante, but also about baile and guitar. He played the guitar very well, by the way, and he even accompanied, among others, the great Antonio Mairena. He not only played the guitar, but also made great guitars. As if all this weren’t enough to merit admiration, the master of Triana was also a very cultured man, a lover of literature, possessing a deep knowledge of many topics. He was also someone with a great sense of humor, yet not that unoriginal and cheap sense of humor so common in Seville and in flamenco, but rather a refined wit, with a natural talent acquired on the streets and in parties. He wasn’t a clown, but an artist who knew a thousand stories and was able to tell them with a wonderful spark. For a few months we were recording a TV series that never aired, together with Juan Valderrama. On recording days, we would go out to some restaurant to have lunch or dinner, but we could barely eat, as we laughed so much with Naranjo and Valderrama’s stories. Listening to them talking about cante was something to behold: the two masters mano a mano. I remember one day when Juan Valderrama told a story about an album recording with Montoya and Mojama, I think it was in the north of Spain, and Naranjo was amazed with the detail of Juanito’s facts. He would even remember the name of the bars where they went for drinks. Naranjito also had a prodigious memory and he knew better than anyone else the Triana of post-Civil-War Spain.

He was able to sing all the Triana styles of soleares and seguiriyas with mastery, not because he learned them from recordings, but because he lived in Triana. Is Naranjo recognized today as one of the great cantaores of Seville? I don’t think so. Certainly those with a solid knowledge of flamenco appreciate the style and the works of the master from Triana, but overall he’s not very well-known, particularly his discography, where he showcases a great variety of palos de cante. Perhaps no one in Naranjo’s time was able to master as many palos as himself, and he excelled in both the basic palos and in the so-called “light palos”(2), although I don’t think there’s such thing as “light palos”, just cantaores who either can or can’t perform them. He could perform them for sure, as he had a superb singing ability. Not just a powerful voice, but he also knew how to sing. Antonio Mairena, Juan Valderrama and Pepe Pinto appreciated him greatly and highlighted his worth as cantaor several times. He shouldn’t be forgotten by Triana or Seville, because he was a great master and one of the best teachers. After retirement, don José taught at the Fundación Cristina Heeren in Seville and one day he invited me to watch one of his lessons. When I arrived, he was teaching a girl from Finland how to sing a soleá alfarera. Believe it or not, the girl mastered that cante de Triana. He was great even when teaching, and that’s one of my favorite things.

- “Naranjito” is the diminutive or endearing form of “Naranjo”, which literally means “Orange Tree”. José Sánchez Bernal inherited the nickname “Naranjito” from his father, an amateur cantaor known as “Naranjito el Municipal”, as he worked as an orange harvester and also as a Municipal Guard (local police)

- “Palos livianos” are palos relatively easier to sing and less dramatic than the “palos básicos” or “palos jondos” (such as the seguiriya and the soleá.) Because of this, it’s actually harder for a cantaor to stand out and impress his audience when singing “palos livianos”.