Waiting for the future (but the future never comes)

A taste for classic or contemporary interpretations isn’t a “decision” you make, but a feeling that installs itself in your head without your realizing it. It’s impossible to resist, and the great wheel of this art-form we all love just keeps turning, headed for new horizons.

A few days ago Manuel Bohórquez, director of Expoflamenco, published an article about the intolerance towards flamenco followers of classic taste, a description that more or less applies to me, as corresponds to my age, although I always try to be tolerant and open-minded regarding new tendencies. Even so, I’m skeptical when it comes to works promoted as “ground-breaking”, “daring” and other such words that let off an odor of “this stuff is new, so don’t even think of protesting”.

But actually, I have more right to protest than others. Okay, I’m old, but the years give you the perspective to navigate through the cultural morass of the new millennium. It seems obvious to me that the flamenco of 2023 often has little in common with that of just 30 or 40 years ago.

In the 1970s Paco de Lucía came on the scene to give us some very important lessons, his buddy Camarón did the same for flamenco singing, and few dancers wasted any time with choreographies the avant-garde sector chalked off as out-dated. I have more right to a tantrum because I’ve sacrificed more than most. Because when I was young, with a wide range of possibilities within reach, I left my country, my culture, my family, my house and my friends, my cat!, all for what was at that time called flamenco, a genre that absorbs you and invades your psyche, making everything else pale by comparison.

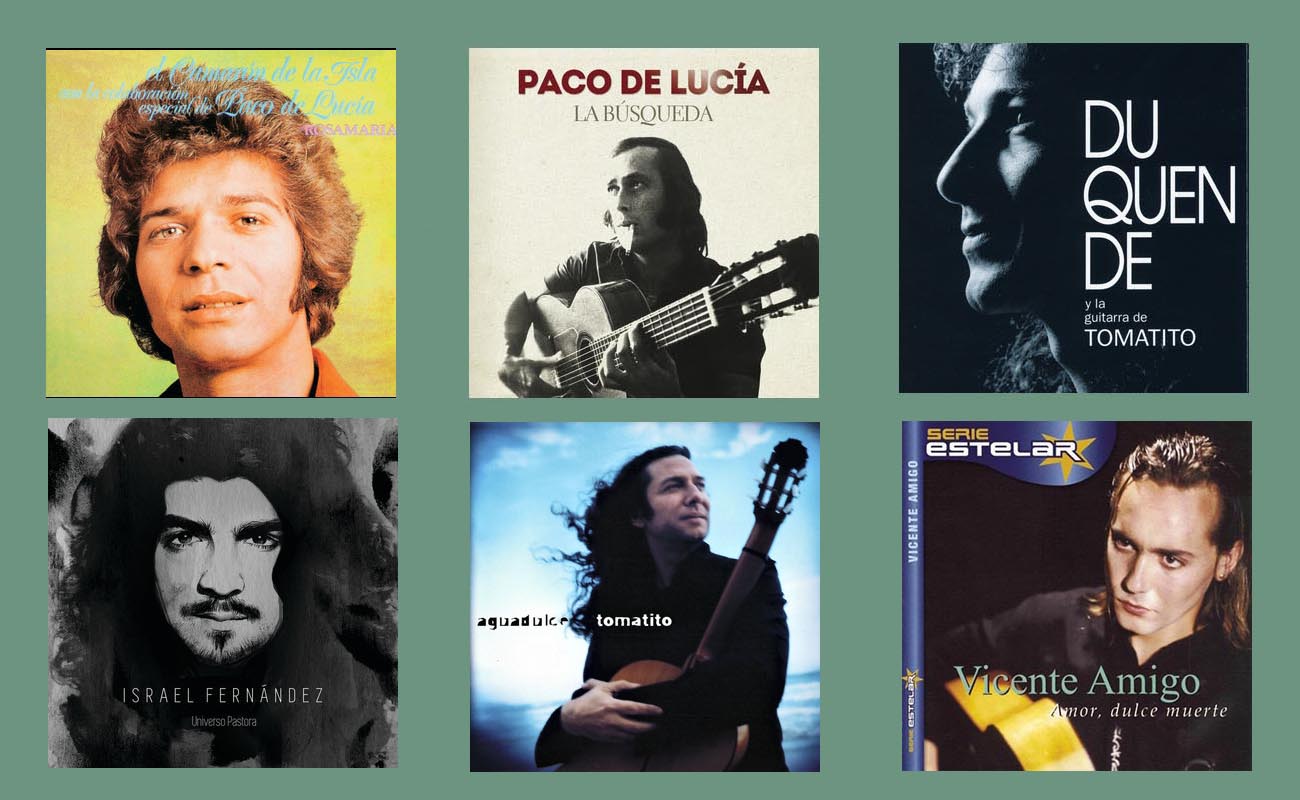

I got to Spain with 10 years of experience, having sung for the José Greco company, a spot formerly held by the much-admired Manolita de Jerez among others. But no sooner did I set foot in Andalusia, as if by some devious plot, the future was being born, displacing the status quo. Paco de Lucía had already ascended to the heights, and at just 23 had announced his intentions in an interview: “I love flamenco very much, and I believe I’m capacitated to make it evolve”. And so he did. But a new generation was already nipping at his heels in the person of Vicente Amigo (1967) and Tomatito (1958), the first, and most noteworthy followers of the path laid out by Paco. Duquende (1965), the first to embrace the Camarón style of singing, was in elementary school so to speak, and the great dancer Eva Yerbabuena (1970), was on the waiting list for kindergarten.

It had been my intention to immerse myself in the most classic sort of flamenco, but the future had already been born, and its ripening and coming of age were inevitable. It’s logical to assume that people are being born as you read these words, artists who, in a short time, will lead the pack of avant-garde flamenco through a future that will seek and defend its own identity, leaving the current one behind in the gutter of nostalgia. Currently, flamenco followers are in a lather over young Rosalía, in both the negative sense –many refuse to accept her shtick– and the positive, because she has an attractive product with flashes of flamenco. Not everything is black and white.

A full half-century after the initial shock wave of Camarón, followers continue to pop up like wildflowers in spring, with young Israel Fernández (1989), from an Andalusian family, being the new kid on the block. His popularity is growing exponentially because he has managed to find his own personality within that of Camarón’s, like the layers of an onion. Likewise, his regular guitarist Diego del Morao, idol of younger guitarists, is escorting us to a future that his father, Moraíto, whom we miss so much, will never see.

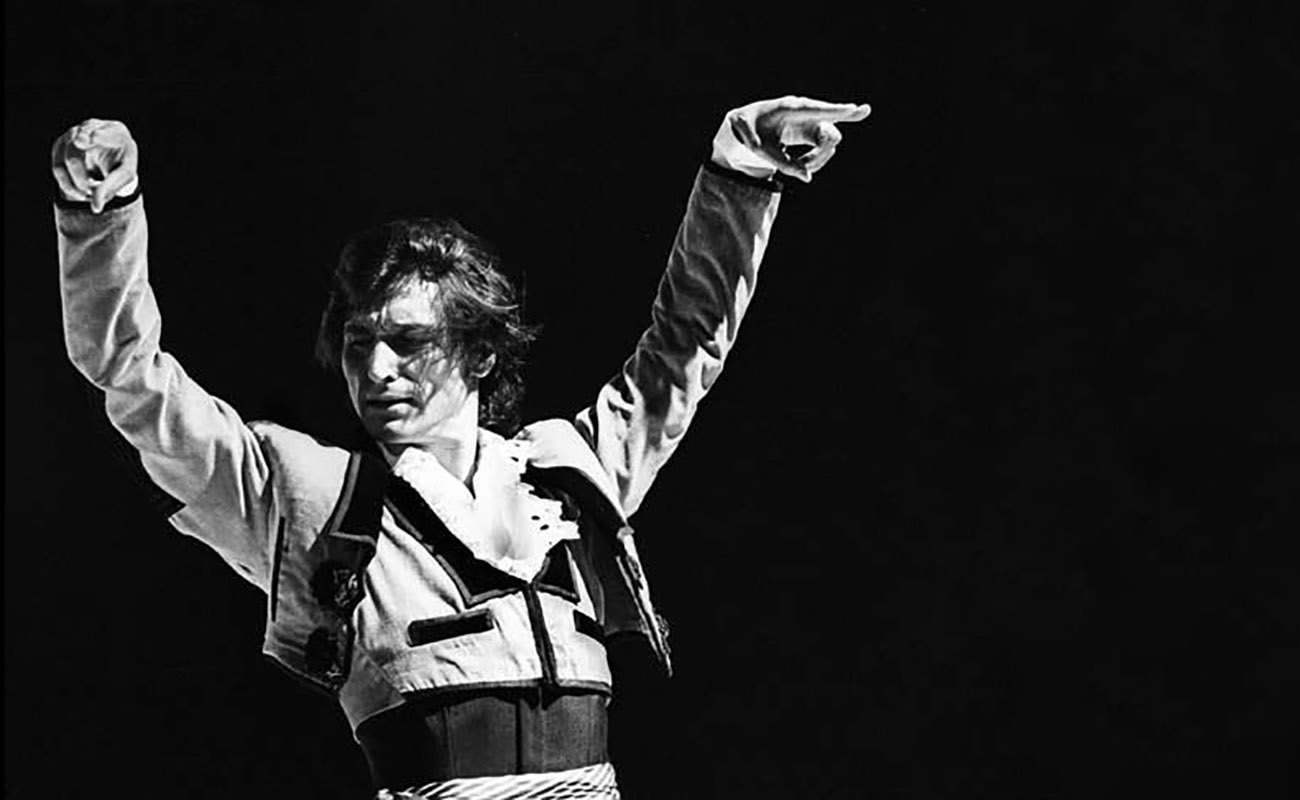

Flamenco dance is in the hands of fearless creators such as Israel Galván and Rocío Molina, while guitar-playing is nearly unrecognizable as guitarists continue to exhibit the after-effects of the “Paco virus” as the man himself used to call it.

A taste for classic or contemporary interpretations isn’t a “decision” you make, but a feeling that installs itself in your head without your realizing it. It’s impossible to resist, and the great wheel of this art-form we all love just keeps turning, headed for new horizons.

Stephen Dick 26 February, 2023

Something that has always made me feel comfortable in the world of flamenco has been the way that, across the community as a whole, listeners and artists embrace and welcome all forms of flamenco that contan the essential spark which may be called sincerity or authenticity.

Enrique Morente was a prime example of this embrace. He could do the most traditional flamenco with a power and an honesty that was immediately recognizeable. He could also do extraordinary experimental works like Omega or El Pequeño Reloj which were equally grounded in traditions both inside and outside of flamenco.

I admit that, as a composer of contemporary flamenco music, I have skin in the game. I know that my newst album, Cantan Los Fuegos, stretches the definition of traditional forms like siguiryas, bulerias, etc. I also know what I had in mind as a drew on those forms to create new works. This music will or won’t be accepted as flamenco by some, but it grows out of a deep embrace of the traditonal flamenco music I’ve been exploring for over 30 tears.