Bulla, burlería… ¡Bulerías!

Of the immense variety of flamenco singing styles, it’s clear that the absolute and unconditional winner in terms of popularity, variety, versatility, and volume of recordings is bulerías.

Ever since Paco de Lucía and Camarón enhanced its popularity, surpassing the rumba, it’s rare to see any flamenco production that doesn’t include some bulerías, and few flamenco singing or dance performances finish their final encore without a touch of festive bulerías.

But it hasn’t always enjoyed such popularity. In fact, it’s a mere adolescent in the great flamenco family. At the beginning of the twentieth century, when other fundamental forms like tonás, fandangos, siguiriya, or soleá formed the backbone of flamenco singing, the bulería was barely in its infancy. With few exceptions, the oldest recordings showcase a rather rudimentary level of simple songs or folkloric themes.

Flamenco scholar Francisco Rodríguez Marín, born in Osuna, Seville, in 1855, claimed not to have known bulerías in his youth. In his book El Alma de Andalucía, published in 1929, he dismissed it as a “new and rare manifestation, without much value”. However, by then, not only had stars like El Pena, El Garrido de Jerez, or José Cepero already recorded variations of the bulería, but also the great Pastora Pavón, “La Niña de los Peines”, had recorded at least half a dozen bulerías with various titles. Rodríguez Marín’s observation is also untimely, considering that in the same year of publication of his book other significant stars such as El Cojo de Málaga, El Gloria, Juan Mojama and the great Manuel Torre recorded bulerías, basically marking the beginning of the reign of this immensely popular flamenco style. Musicologist and flamenco expert Hipólito Rossy, born in 1897, also claimed to have known few references to the bulería until the second decade of the twentieth century, although he added, with a disdainful attitude, that “some” did indeed sing and dance it.

RHYTHM

For music scholars, the rhythm of the bulería is the same as that of the soleá, although it’s more upbeat or brisk. In practice however, and for traditional performers, there’s barely any artistic relationship between the two forms. In its beginnings, the bulería followed a simple rhythmic cycle that repeated in measures of six. However, it gradually adopted what some call “amalgamated rhythm”, two measures of three and three of two, totaling twelve. But the custom of associating numbers with rhythm only takes us to a rudimentary level of understanding because flamenco interpreters work on the pulse or accents independently of any intellectualized perspective of sets of twelve. Specifically in bulerías, the rhythm is felt like a merry-go-round with rings which are the accents hooked by singer, guitarist, or dancer, each in their own way, forming a powerful internal tension that gives the characteristic energy which is the essential dynamic of bulerías.

Although the bulería rhythm serves as a universal framework within flamenco, there are unmistakable local variants. In Jerez, it’s more on the brisk side, in Utrera, it’s more leisurely, and in Lebrija, there’s a sway reminiscent of ancient ballads also cultivated in this region.

Bernarda de Utrera canta y baila por fiesta con su sobrino José en la Feria del Flamenco, 2001. Foto: Estela Zatania

DANCE

If flamenco dance was cultivated in London and Paris, as some researchers suggest, the dance of bulerías, that brief rhythmic bit of every singer, guitarist, or dancer, is indigenous and authentic. On the big international stages, we see elaborate choreographies, intricate footwork, extravagant costumes, beautiful women and handsome men executing technical feats with precision: soleá, siguiriya, tangos, alegrías, and taranto are among the most performed show dances at present. By contrast, bulerías dancing has developed on-site in a non-commercial environment: neighbors’ houses, taverns, local stores… The best festive dancers are masters of minimalism, of subtly suggested gestures and grace. The much-admired Anzonini del Puerto (Manuel Bermúdez Junquera, 1918-1983) used to say that those who dance bulerías best are those who move the least.

VOICE

There are only a handful of styles that could be called “classic”, but bulería enjoys a unique condition in the flamenco singing repertoire: one can sing bulerías or sing in the style of bulerías. When Pastora Pavón sings “Cielito Lindo”, Pepe Marchena his “Cuatro Muleros”, Bambino’s “El Poeta Lloró”, Porrinas de Badajoz “Ojos Verdes”, Lole’s “La Mariposa”, Camarón “La Leyenda del Tiempo”, they are singing in the style of bulerías. That is, they are adapting a song, whether it’s original, folkloric, or popular, to the festive rhythm of bulerías. Traditional singers use these “derivatives” to add more variety to their performance, often interspersing some classic short-form bulerías.

There have been many singers specialized in bulerías, but one figure casts a giant shadow over all the rest: Francisca Méndez Garrido, “Paquera de Jerez” (1934-2004), due to her rhythm, power, and ability to deeply move audiences with a style that some dismiss as “lesser”. Her disappearance in 2004 has left a difficult void to fill. Other names to consider, besides those already mentioned, are Bernarda de Utrera, Terremoto de Jerez and Perla de Cádiz, among many others.

GUITAR

The solo or concert guitarist, when playing bulerías, utilizes a wide range of musical options, and there are no limits other than those of his own imagination. Paco de Lucía pioneered new paths in bulerías, and nowadays, young prodigies are exploring unknown territory. Manuel Moreno Jiménez “Manuel Morao” (Jerez de la Frontera, 1929) and Manuel Fernández Molina “Parrilla de Jerez” (Jerez de la Frontera, 1945-2008) have been great creators of the Jerez sound in bulerías. Nor can we overlook the Granada school which reached its peak with Juan and Pepe Habichuela (1933-2016 and 1944 respectively) and Juan Santiago Maya “Marote” (1936-2002).

If the other flamenco forms are full glasses where interpreters go to drink, bulería is a great empty glass that each one fills as they please.

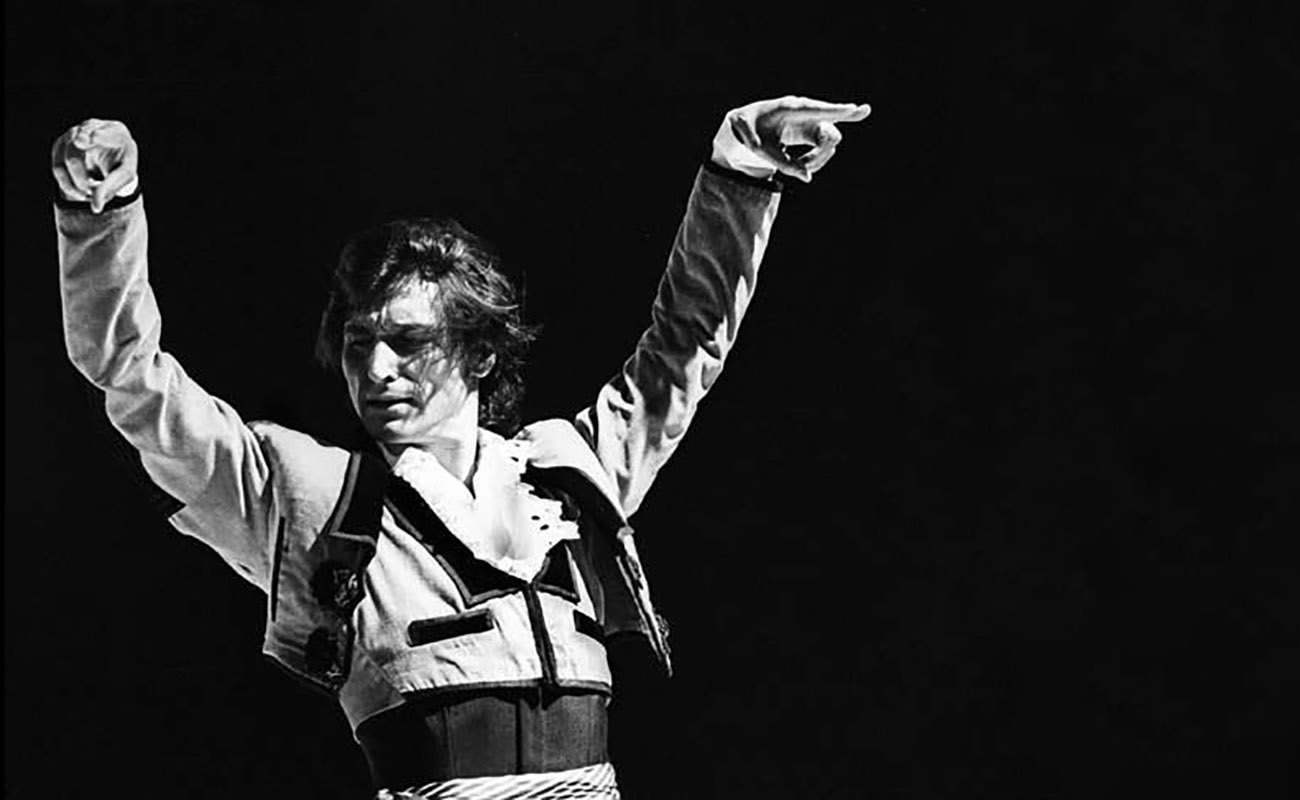

Top image: Baila Tía Juana la del Pipa, canta Terremoto. Archivo: Diego Alba