Grandpa and La Alameda de Hércules

Nowhere in the world there has been such a concentration of flamenco artists as at La Alameda de Hércules from the mid 1800s to the mid 1900s.

-Grandpa, who decides whether a flamenco artist is honored or not? For example, who decided not to have anything in memory of Silverio in Seville, but to have a statue of Antonio Mairena instead? I’m not saying Mairena didn’t deserve it, but why isn’t there any statue of Silverio, who should have a memorial in every city of Andalusia?

-I can explain this easily. At the time of Silverio, in the 1800s, flamenco artists weren’t much valued by society as they are now. Silverio was the greatest of his generation, and he was also an important entrepreneur. He was loved and respected in Seville not only by the aficionados, but also by fellow artists, Gypsy or not. Yet, when Silverio died in 1889, the cafés cantantes were discredited in Seville, including his own. Indeed, his café had already closed down when he died in 1889. So he fell into oblivion. In those days, no one put monuments in honor of flamenco artists, or named streets after them.

-Yet, grandpa, eventually the time came when artists started being honored, but no one in Seville lifted a finger to acknowledge Silverio as one of the pioneers of flamenco like he was. Why?

-Because that’s how things are in Seville. Silverio should have a statue at the plaza of La Alfalfa, where he was born, but the reality is that no one has taken the initiative, and monuments happen when the aficionados lobby the authorities until they get the green light. Antonio Mairena has a statue in Seville because his admirers, the mairenistas, made it happen. The same goes for Niña de los Peines and Caracol. No one has done anything to erect a memorial honoring Manuel Vallejo, who was perhaps the most important cantaor of Seville and was awarded the first Golden Key of Cante of the 20th century.

-Someone once suggested filling La Alameda(1) with statues of flamenco artists, but that never got started and it’s now all forgotten.

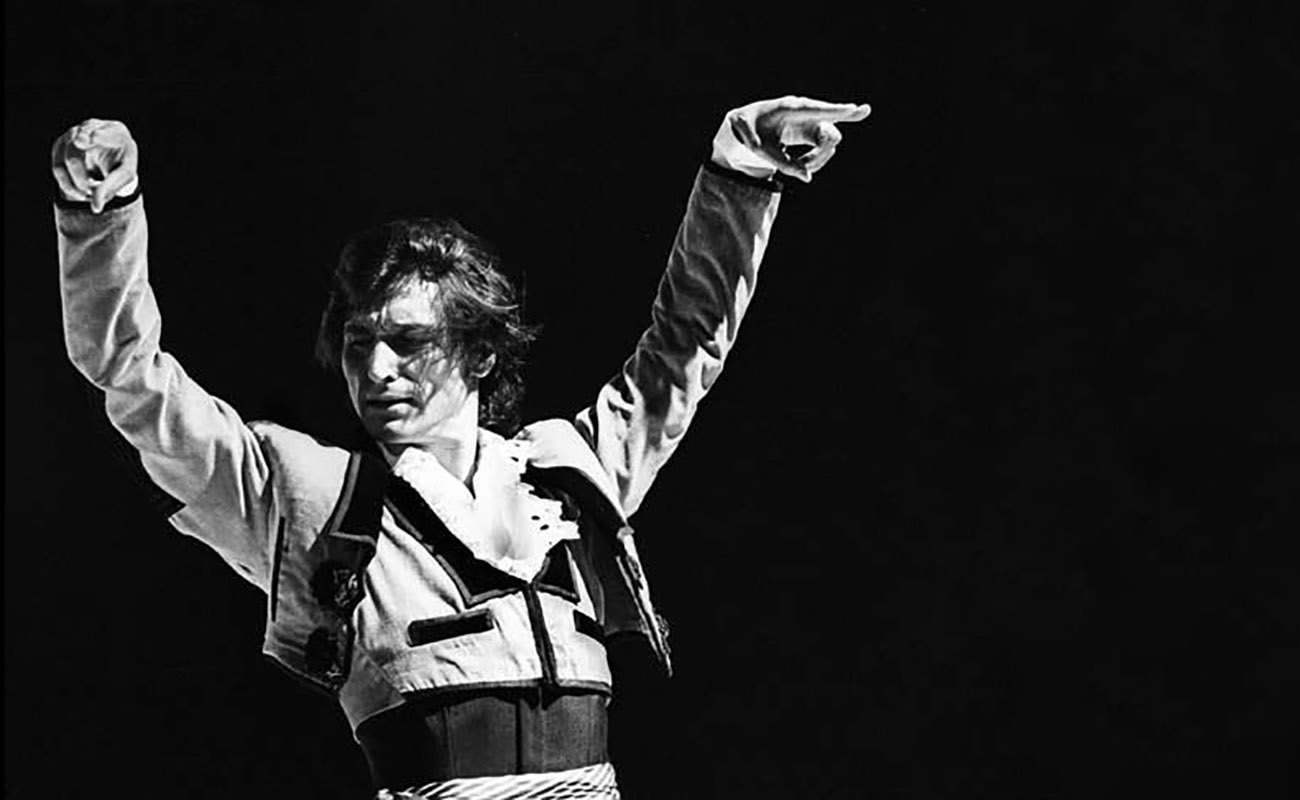

-Lorca once dreamed with having a statue of Manuel Torres in La Alameda, featuring real hair. Manuel had a very handsome black hair, beloved by half of Seville. He was La Alameda de Hércules’ king of cante. Yet, one day he was performing in a party and he couldn’t finish a seguiriya he was singing, because he was dying of tuberculosis. Tomás Pavón was in that gathering, and the genius of Jerez told him “Tomasito, finish it up, because I can’t”. That’s how, that day, Tomás became La Alameda’s new king of cante. Juan Lafita, the painter from Seville, was there that night, and he wrote about that scene, which in his opinion was the moment when Torres passed cante’s baraka to Tomás.

-So, grandpa, about filling La Alameda with statues, I guess isn’t happening?

-That would be a barbarity, besides being unfeasible. There would have to be so many statues, for so many artists. Yet, they could make one single monument honoring all the artists who were born or worked in that corner of Seville. Did you know that Silverio also lived at La Alameda? Not just in the neighborhood, but in the actual La Alameda de Hércules street. In 1870, this genius was living in that street because he was already managing a café cantante close by, and he used to live near his cafés, I supposed because he wanted to keep an eye on them. Then he moved to Potro street, which was also in La Alameda district, where many years later Pastora Pavón and Manuel Escacena lived as a couple.

-How important was La Alameda de Hércules for flamenco?

-Look, Manolito. Nowhere in the world there has been such a concentration of flamenco artists as at La Alameda de Hércules from the mid 1800s to the mid 1900s. Nowhere. There were whole tenements (“casas de vecinos”) where only flamenco artists lived, such as the number 8. Every flamenco artist, from the very origins of this art, has lived or visited this place. The quality of singing at La Alameda was unlike anywhere else in the world. It was the best school of cante in history, and also of baile and guitar, of course. Yet, is there any memorial about any of this? Nothing. Well, two badly located statues, those of Pastora and Caracol, besides the statue of the bullfighter Chicuelo.

-What would you do, grandpa?

-I would put up a monument, just one, honoring that place and those who made it great and flamenco. I would also create a flamenco archive center. Say, in the house where Silverio lived, which is still standing. If Seville wasn’t shameless, which it is, this would have been done many years ago. Yet, although Seville is one of the main cradles of flamenco, it shows very little interest about the history of this art. Odd, isn’t it? But that’s just how it is.

-¿Which artists, among the oldest ones, performed at La Alameda?

– Miracielos and El Raspao, Ramón Sartorio and José Lorente performed there in the mid 1800s. María la Andonda gave birth to her first son at La Alameda in 1864, when she lived with El Fillo hijo. In those days Maestro Pérez was already the most important guitarist of La Alameda. The Parrala sisters, from Huelva, came later and, from the 1870s on, the place was teeming with artists who had come from all over Andalusia and beyond: La Carbonera, La Juanaca, Paco la Luz, Frijones, La Chata de Madrid, El Canario, El Perote, Enrique Ortega, La Mejorana, Josefa la Charrúa, La Macarrona, La Malena, Chacón, Manuel Torres, El Gloria, Currito el de la Jeroma, los Triano de Écija, AntonioMoreno, La Moreno de Jerez… It’s an endless list.

-You’re a complete encyclopedia grandpa.

-That just goes to show how old I am, Manolito.