Technique and duende

We often hear people say that technique and duende are mutually exclusive in cante jondo, and I think this should be put into context. According to Manolo de Huelva and many other flamenco experts, the cantaores with the best singing technique were Antonio Chacónand Tomás Pavón, at least in those days. Does that mean they didn’t have duende? I don’t thing so. Although duende is something very subjective, Chacón’s cante immediately gets into my

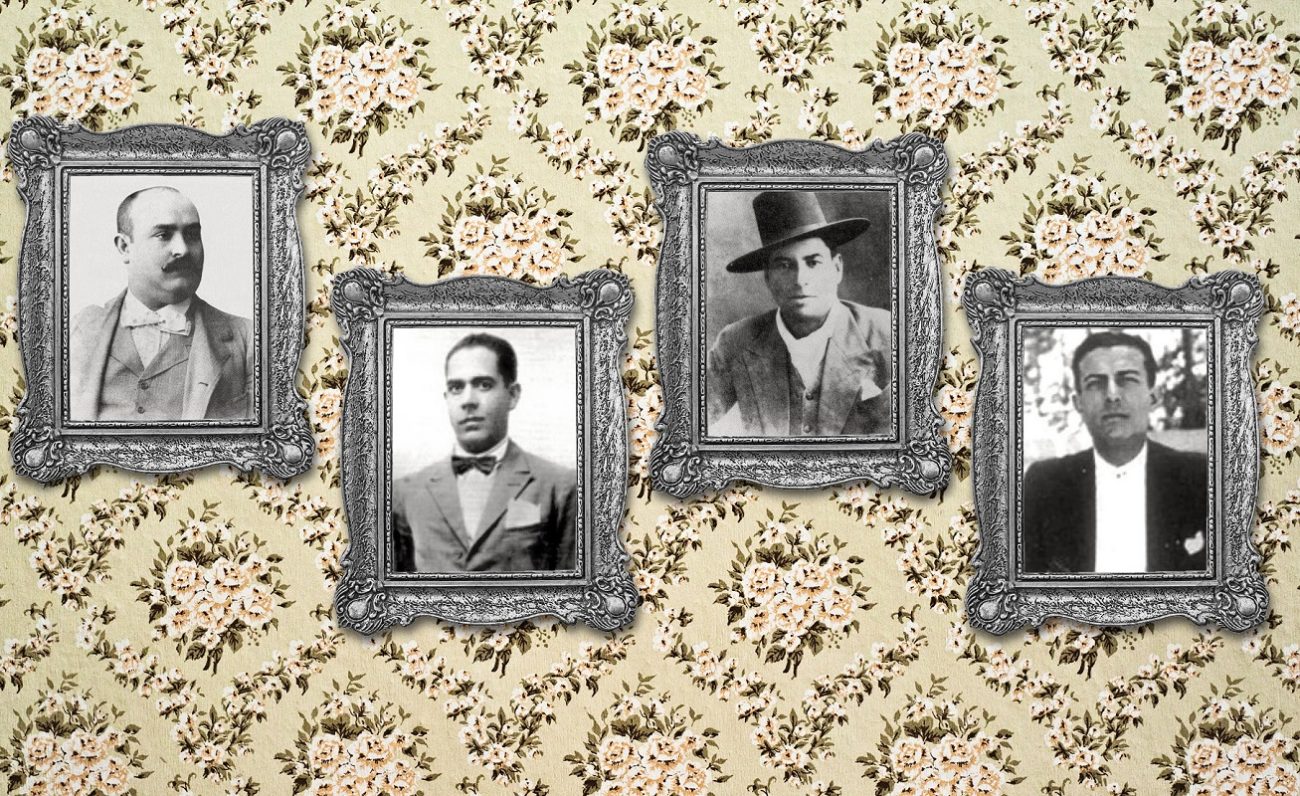

We often hear people say that technique and duende are mutually exclusive in cante jondo, and I think this should be put into context. According to Manolo de Huelva and many other flamenco experts, the cantaores with the best singing technique were Antonio Chacónand Tomás Pavón, at least in those days. Does that mean they didn’t have duende? I don’t thing so. Although duende is something very subjective, Chacón’s cante immediately gets into my heart and soul whenever I listen to his recordings. Perhaps that’s because I like well-executed cante and this master from Jerez was the best of them all, at least among those who made recordings in his time. If we listen to other cantaores of that period, we’ll notice the big difference between Chacón and everyone else. No to mention Tomás. Only Manuel Torres (who was one of his teachers), and Juan Mojama could match the singing quality of the younger brother of Pastora.

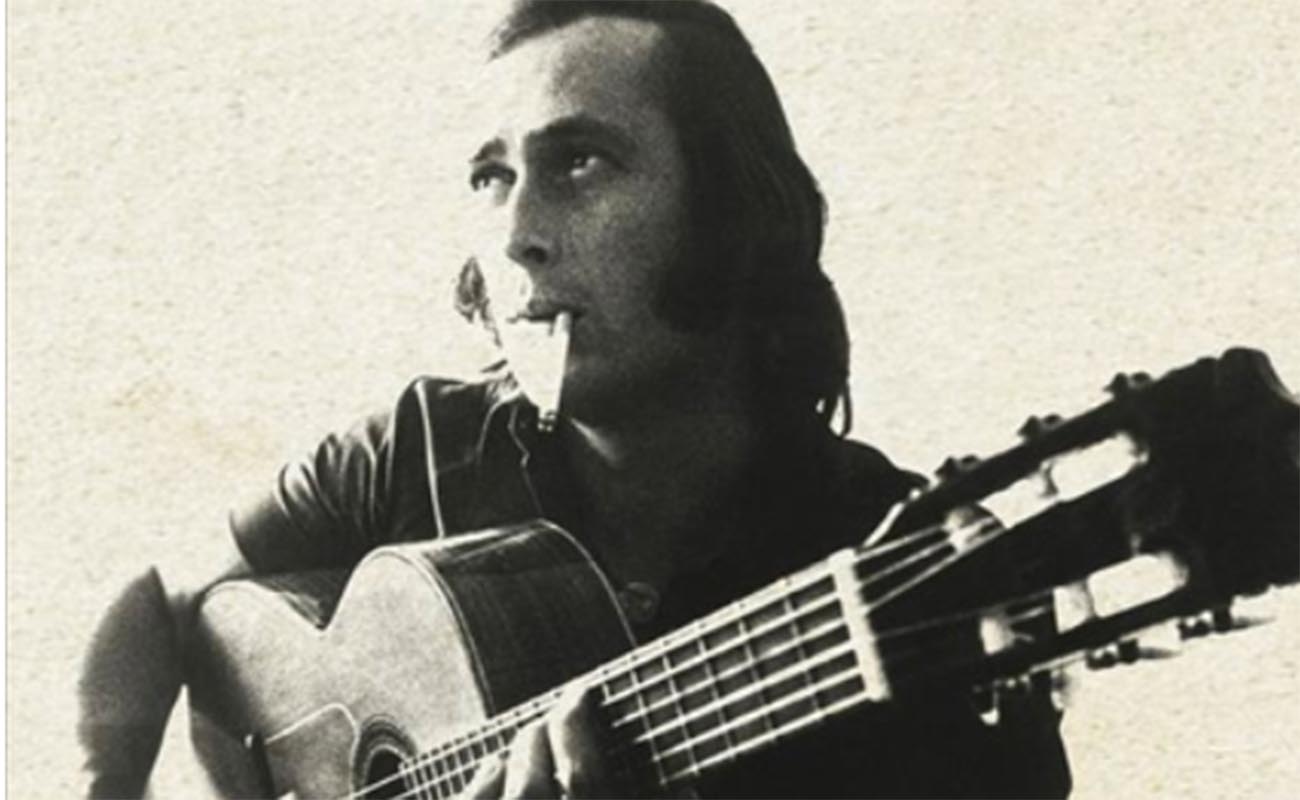

Not only technique is compatible with art, but technique is an art in itself, or a way to make art. When we highlight the art of Antonio el Chocolate, we often forget that he had a great technique, too, just like Antonio Mairena. I talked a lot about cante with Chocolate and he was clear that he wasn’t just an inspired singer, a cantaor de pellizco. “I sing with inspiration, with pellizco, but I have a proper breathing technique and I put the verses in the right places”, he told me in one occasion when I interviewed him. He accepted his anarchy as a virtue and not as a defect, what shows that he was much more intelligent than people think. He wasn’t as raw. What happens is that he had many hard life experiences since his childhood, when he joined Bizco Amate singing along the tenement yards hoping to get some coins thrown from the windows and balconies.

In one of these occasions when they sang and begged for coins, the cantaor Pepe Aznalcóllar was in a balcony and Bizco told him: “Pepe, toss me a peseta, come on!”. Aznalcóllar was a joker and he told him that he would not, because “the wind will carry it away”. Bizco, in a momento of brilliance and, certainly, frustration too, replied: “Toss it inside a bread roll, then!”. Chocolate experienced those things and his cantecouldn’t possibly be like that of an opera singer raised comfortably in a good home. He sang in the same way he had lived. Let’s remember the answer of Manolito el de María, the Gypsy cantaor from Alcalá, when asked why he sang the way he sang: “Because I remember all the things I’ve been through”.

The other day I listened to Manuel de la Tomasa sing at Peña Torres Macarena, in Seville, and in some moments, I was greatly moved as he sang por seguiriyas. Yet, Manuel grew up without experiencing any deprivation or major suffering and was raised by excellent parents. His only defining life experiences would been those he had at his home, but there was a moment when he conveyed great suffering as he sang, and we could feel his pellizco and jondura, that emotion unique in cante jondo, because if it doesn’t touches our hearts is not cante jondo. Manuel has a good, natural technique, and moments of duende that are so necessary in an art so communicative and heartfelt as flamenco.

Translated by P. Young