Has Carnival killed the flamenco star?

Flamenco owes a lot to the Carnival of Cádiz, whose verses many times featured in the repertoires of flamenco’s greatest singers. Yet, the Carnival’s success threatens to absorb the rich musical talent of this province, to flamenco’s detriment.

Besides the renowned wit and good humour in full display during the celebrated Carnival of Cádiz, one of the things that the visitors find most surprising at this time of the year is the sheer amount of people — both in the capital and around the province — with good talent for singing and playing the guitar. Several hundreds or even thousands of aficionados take part in the carnival’s chirigotas, comparsas and coros, often displaying extraordinary vocal abilities and outstanding technique.

Carnival and flamenco are two musical forms that some consider to be opposites but have historically evolved side by side. Research by academics such as Javier Osuna are conclusive in this regard, and I will certainly not dare to contradict his findings, from flamenco’s “borrowing” of the Carnival’s tango to the presence of carnival verses in the repertoires of many flamenco stars such as Marchena, Mairena, Pericón, Manolo Vargas, Chano Lobato, Selu de Cádiz and Mariana Cornejo, to the participation of renowned flamenco artists — such as Espeleta, Joaquín el de la Paula, Camarón and Juan Villar — in several Carnival ensembles. It has been a symbiotic relationship, with each genre enriching each other through the ages.

Yet, the carnival lasts just a couple of weeks, or a few months at most, if we count the rehearsals. From such a formidable musical quarry we might expect that Cádiz would provide a multitude of flamenco artists, even if just indirectly or statistically. However, this is not the case. David Palomar, a renowned cantaor from Cádiz who also has an extensive experience performing at carnivals, could be the exception that proves the rule. What about the others, though?

«Just like the story of video killing the radio star, the carnival threatens to kill the flamenco star by, let’s say, diverting vocations. Yet perhaps we should not be too dramatic: the fact that things are going so well for the carnival is a good thing for music in general and for Cádiz in particular»

The explanation to this apparent mismatch is to be found in the recent evolution of both genres, and in the different demands of each. Carnival music is welcoming and does not demand significant sacrifices from the initiated. It is often shaped by friendship and wit, and the choir structure dilutes, or at least distributes, the responsibility of each performer. Although there are some top-level ensembles, such as those that take part in the contest at the the Great Falla Theater, the Carnival’s temple, many others are below amateur quality, yet suffer no harsher criticism than the indifference of the public.

Cante flamenco, on the other hand, is an extremely demanding discipline. No one in their right mind would dare to sing in a tablao of a neighborhood association without feeling an obligation of knowing about flamenco singing and having a solid vocal control. In order to just perform soleás, seguiriyas, tangos or bulerías — not even trying to find success or acclaim — many years of studies and many hours of careful listening and preparation are necessary, unless one is lucky enough to have grown in the midst of a family of flamenco artists.

The difference between the carnival and flamenco genres when it comes to guitar playing is even greater. Although guitar playing in carnival’s comparsas has become more sophisticated in the last few years, there is no comparison with the slavish need to practice seven or eight hours per day demanded by the flamenco guitar. Considering both the physical effort and the time invested, a flamenco guitar player is comparable to an elite athlete.

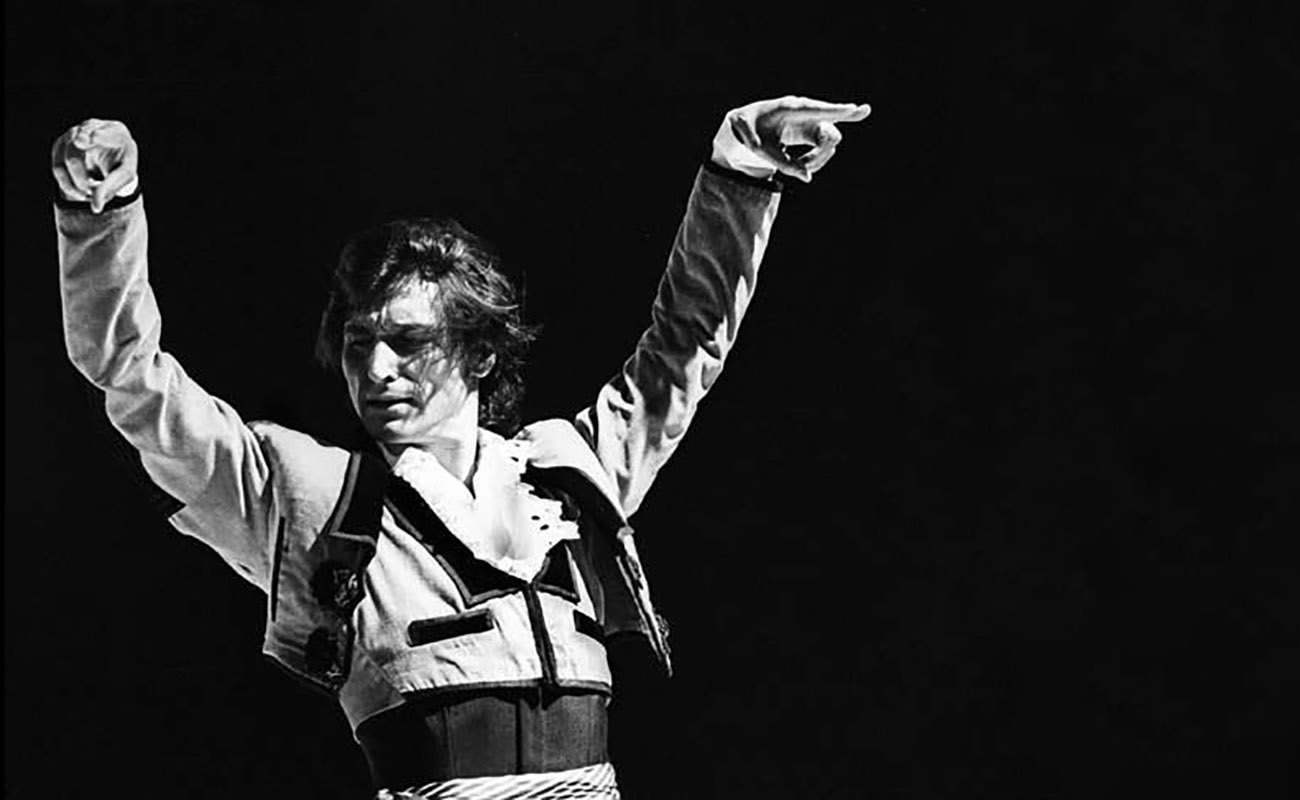

All that effort and commitment is necessary to just achieve an acceptable level, to join the crowd. Performing on a stage requires being impeccable, having something to say, being original. Failing to meet expectations would make any critic, such as yours truly, watching comfortably from his seat, chastise you mercilessly without taking into consideration all the sacrifices you have made. Flamenco is unfair like that. Maybe all art genres all like that, but this is particularly true with live performances, where the “here and now” allows nothing but a very thin margin between glory and failure. For each musician, such as Jesús Guerrero, to give a recent example of unquestionable success, there are many hundreds of shattered dreams.

«Indeed, anyone with basic talent for singing or playing the guitar would think twice when it comes to decide between carnival and flamenco. Without trying to minimize carnival performers, it is the difference between taking up a hobby (that we can give up whenever we want) or entering the priesthood.»

We may argue that popularity, fame and money are also a factor in the carnival/flamenco imbalance of artists. Interestingly, in the last few decades the Carnival of Cadiz has achieved such renown that its most notable performers have become celebrities. Taking part in the carnival is not just fun, it is also profitable and great for self-esteem. Who would not rather achieve all of this by taking the easiest path?

Indeed, anyone with basic talent for singing or playing the guitar would think twice when it comes to decide between carnival and flamenco. Without trying to minimize carnival performers, it is the difference between taking up a hobby (that we can give up whenever we want) or entering the priesthood.

All of this may lead us to conclude that, just like the story of video killing the radio star, the carnival threatens to kill the flamenco star by, let’s say, diverting vocations. Yet perhaps we should not be too dramatic: the fact that things are going so well for the carnival is a good thing for music in general and for Cádiz in particular. Regarding flamenco, let’s hope that it continues to attract the new generations, with the likes of Martínez Ares and Camarón featuring in their phone’s playlists. Perhaps that might inspire them to start singing por alegrías one day…

Translated by P. Young