Is flamenco Spanish classical music?

I insist on pointing out an important feature shared by both flamenco and classical music: the prevalence of multiple versions.

This is one topic I have already written about in previous articles. Since this is a matter with various perspectives, today I will focus on one aspect worth exploring that I have not previously dealt with, and I hope ExpoFlamenco readers will find it interesting. Here it goes.

In Spanish we call “música clásica” (also referred by some as “música culta” or “cultivated music”) what the English call “art music” and the German call “kunstmusik” (literally “art music”) which in my opinion is a much more accurate way to describe the type of music I call “academic”. However, to understand the context of this article, let us define “classical music” as the one composed at least a century ago of before, following academic principles of composition, and made widely known in time and space by the various classical interpreters. That is, the different works of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms… to name four great masters.

What about the flamenco cantes credited to La Serneta? They were also, in a way, “composed”. That is, the melodies that define them as such were created within a rhythmic-harmonic template that we can identify as a soleá (with their different series of accords according to the variant). That is, they are also an artistic matter, albeit with an oral instead of an academic origin, but art nonetheless, rich in culture as any lied by Schumman or Mahler. That is why I have been for many years pointing out to whoever wants to listen that flamenco’s repertoire is simply Spanish classical music, mostly created during the so-called Romantic period, which in Spain lasted well into the 1930s, and which was passed on orally instead of in written form. That is the great difference, which is a rather minor thing. The content is as “cultivated” as that of any other music piece defined as such.

«Flamenco’s repertoire is simply Spanish classical music, mostly created during the so-called Romantic period, which in Spain lasted well into the 1930s, and which was passed on orally instead of in written form»

This is really a matter of the social status of those who coined each musical expression. There is a sort of elitism that has always (particularly after the rise of the bourgeoisie) conditioned the opinion of what is flamenco and what is classical music. The culprits are generally the cultural elites which, with their misplaced modernist attitudes, still expressed ideas such as those by the unfortunate Spanish minister Ernest Lluch who, speaking about a flamenco conference organized by Félix Grande at Madrid’s Complutense University, bluntly stated that “allowing flamenco into the classrooms discredits the University”. Small actions can have big consequences. Such backward mentality is what has caused the greatest harm to flamenco. Yet, flamenco artists are also to blame, with some even shunning the “artist” label, believing that an excessive melodic sophistication tainted the essence of cante flamenco. Even Pepe Marchena thought that it was him who made flamenco palatable for the elites, taking this genre from taverns to more upscale venues.

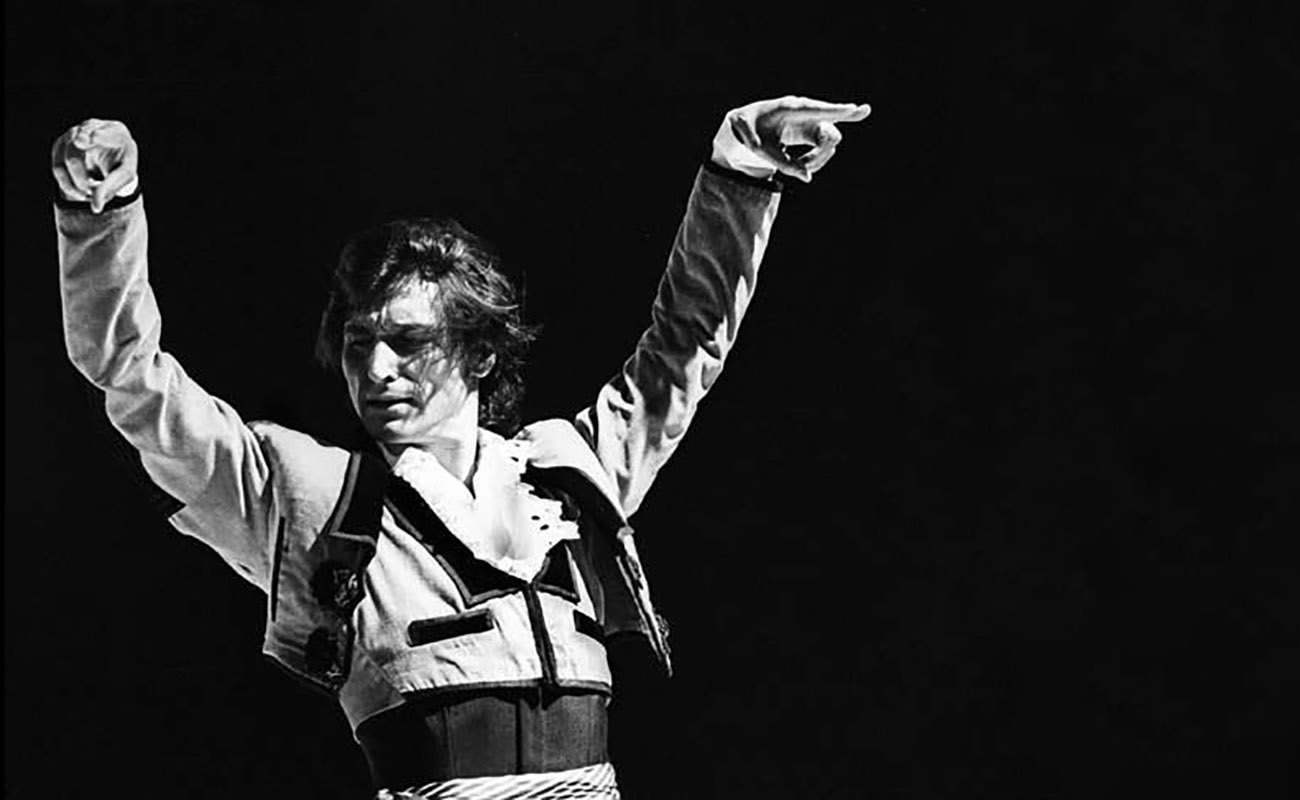

Composing is an intimate and rather lonely activity. Traditionally, flamenco is generally composed with a guitarist or with the cantaor himself playing the guitar. In my opinion, cantaores must know how to play the guitar, if only to tune themselves and ensure the faithful reproduction of the cantes. I remember as if it were yesterday Enrique Morente with his guitar, mumbling the cantes he composed in the sofa at his house in Camino del Monte, where he lived in the early 90s. In fact, there is not much difference between a lied by of Brahms and a cante by El Mellizo. The “flamenco composer” models the cantes by putting into music lyrics of his own or of an anonymous author, within the framework of a specific style, just like Schubert did. In flamenco, that framework is defined by the palos (soleás, seguiriyas, tientos, etc.). In Schubert’s case, that framework was defined by the aesthetic parameters of the traditional classical lied of the early 1800s, having composed over six hundred lieds during the 31 years of his life.

«In fact, there is not much difference between a lied of Brahms and a cante of “El Mellizo”. The “flamenco composer” models the cantes by putting into music lyrics of his own or of an anonymous author, within the framework of a specific style, just like Schubert did»

Those who like cante flamenco can recognize the very different versions of countless cantes, those shaped by the likes of Frijones and Silverio, now in our memories (and records) for ever. Just like there are no identical versions of Mozart’s Turkish March, regardless of the written score, there are no identical versions of the malagueña del Mellizo. Here lies the richness of classical music. Even as many believe it is static and inflexible because it is written in music sheets, this is far from the truth. Written scores also allow for innumerable reinterpretations, not of their tunes, but of their articulation, dynamic, intensity and tempo, as these factors are for the interpreter to freely decide. How boring would opera, for example, be if the Pavarotti and Domingo versions of Tosca were identical. We can say the same about the malagueña grande de Chacón performed by Chacón himself and the one by Morente. Enrique’s album Homenaje a D. Antonio Chacón is a great example of the reinterpretation of classic cantes created by a genius like Chacón. If we listen to the original versions and compare them with the ones by Morente, we will notice significant differences between them. That is why I insist on pointing out an important feature shared by both flamenco and classical music: the prevalence of multiple versions. When I was director Deutsche Grammophon, the then-mayor of Madrid, Gallardón, reproached me for competing against myself by releasing at the same time two versions of Liszt’s Sonata in B minor, one by Khrystian Zimerman and the other by Ivo Pogorelich, what prompted me to create a marketing campaign titled “Para gustos hay versiones” (loosely translated as “For each taste, one version”, a play on words of a popular Spanish saying). The same happens in flamenco, where some people like the seguiriya del Viejo de la Isla with the lyrics “Por tu causita me veo…” sung by por Manuel Torres, while others prefer Pastora ‘s version, and others still Cagancho’s. That is the best thing about artistic music.

Translated by P. Young