Flamenco: our shared heritage

Those who claim to perform flamenco, demand respect for what they do, while the purists also demand respect because they believe that defending and protecting what they love, traditional flamenco, is a worthy cause. Well, the former call the latter “obsolete”, while the latter call the former “crazy”. It’s an ongoing war with no end in sight. As Jafelin Helten rightly

Those who claim to perform flamenco, demand respect for what they do, while the purists also demand respect because they believe that defending and protecting what they love, traditional flamenco, is a worthy cause. Well, the former call the latter “obsolete”, while the latter call the former “crazy”. It’s an ongoing war with no end in sight.

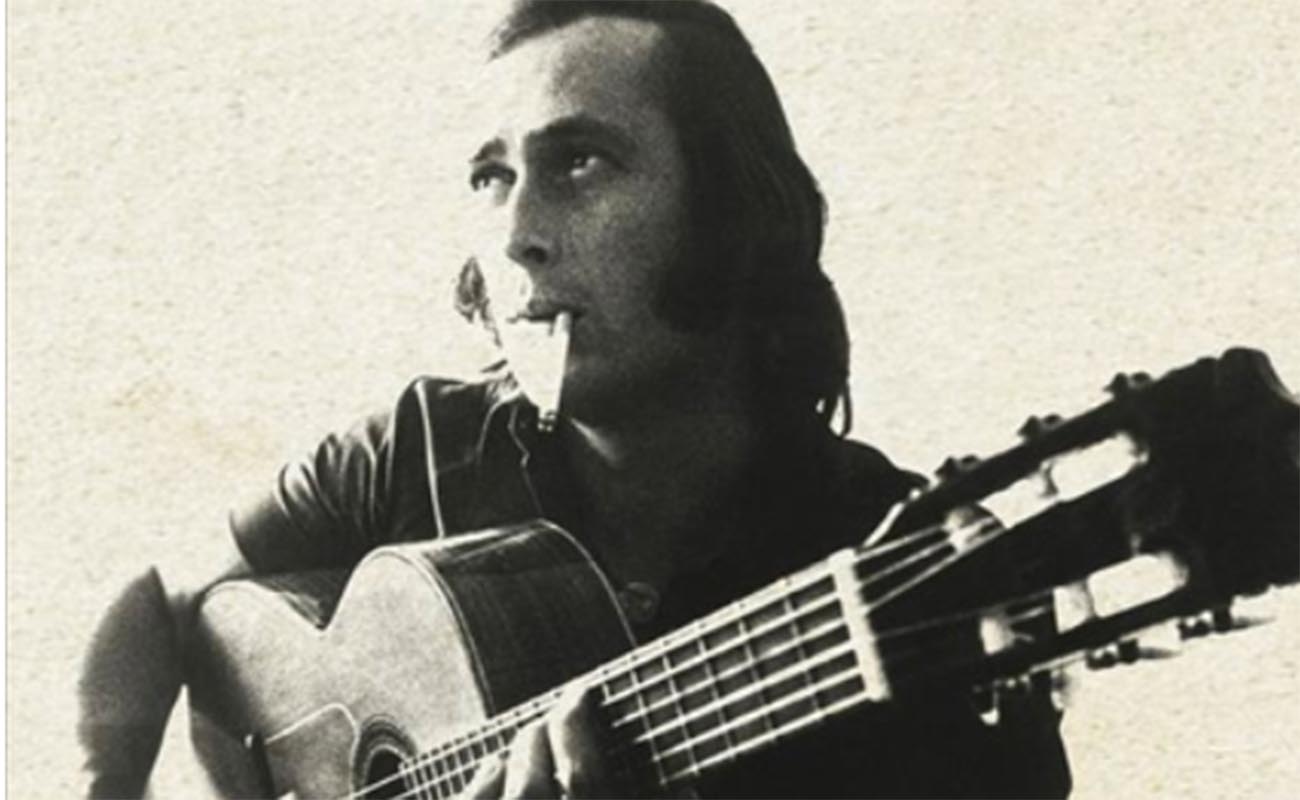

As Jafelin Helten rightly points out, flamenco is more than a musical genre or a dance style: it’s a lifestyle. Someone may learn how to play the guitar and perform a rondeña or a taranta, but it would be just that, a mere performance, unless they experience flamenco, living flamenco as the ancient culture it is, as a way of life. No one has the right to call “flamenco” whatever they want or believe it is. Besides, it’s easy to fool people, because sometimes it’s hard to know what is flamenco and what isn’t.

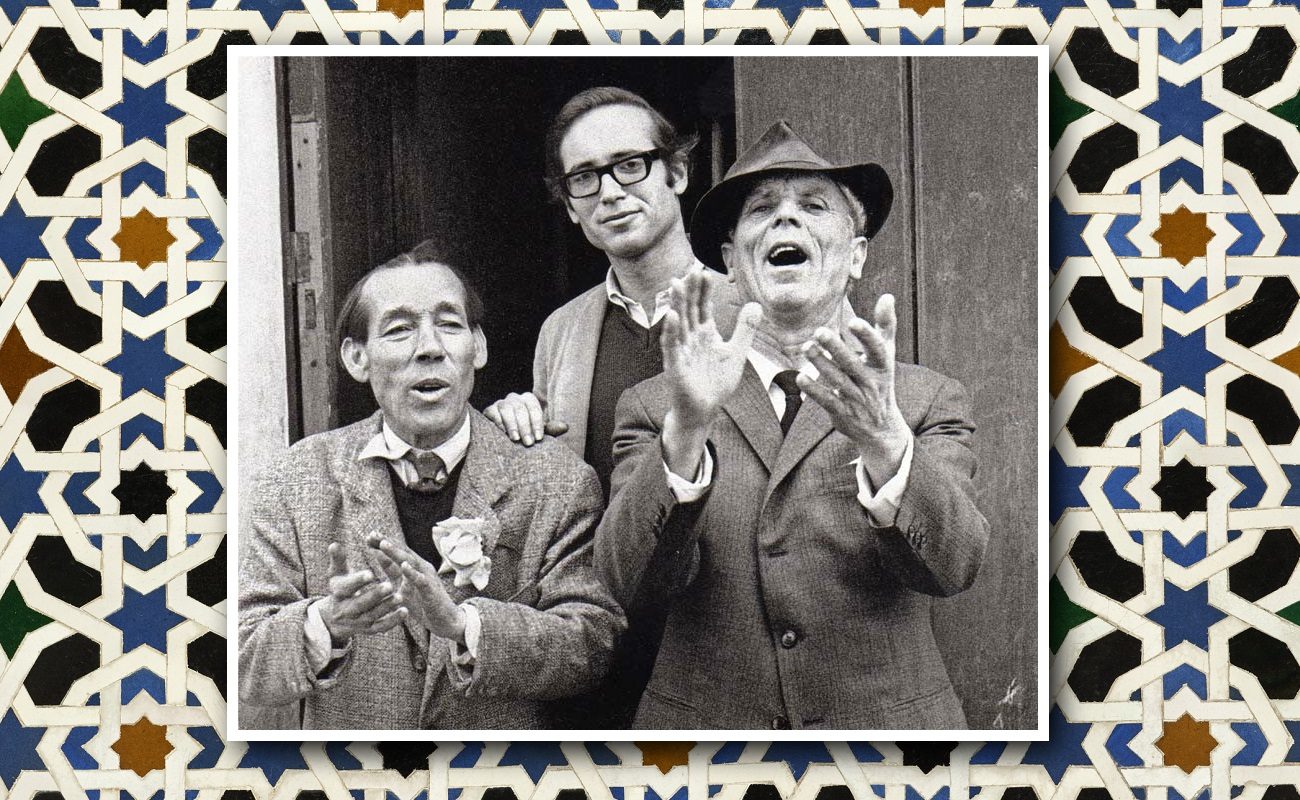

Some people even say that a malagueña performed by Chacón is “less flamenco” than a soleá sung by Perrate de Utrera, just to put one example of clear disorientation. Why would Chacón’s malagueña be regarded as “less flamenco”, just because Perrate was Gypsy and Chacón wasn’t? Perrate experienced flamenco all his life, but so did Chacón, too. Both absorbed the tradition of towns with a long flamenco history, one in Utrera and the other in Jerez. I wonder how many of those who dismiss Chacón as a tenor or singer of popular songs (as opposed to a flamenco cantaor) know anything about his life or his artistic career. That’s something essential to be (as some people call themselves) flamenco. There are even t-shirts with the slogan “I am flamenco”, just like the t-shirts worn by soccer fans. As if wearing a t-shirt would be enough to “be flamenco”. Nonsense.

A while ago I wrote in this blog about the risk of flamenco becoming something vulgar, without art, and that is actually happening. Flamenco, all flamenco, is a cultural heritage, and no one, not even in the name of “artistic freedom”, has the right to threaten this heritage. The Giralda bell tower, landmark of Seville, has already been built, and it’s a jewel of architecture. If someone doesn’t like it, they can build their own tower, instead of trying to modify the existing one. Whoever wants to perform Chacón’s Del convento, las campanasor Manuel Torres’ Los días señalaítos, they can do so, with their own imprint, but they should never destroy anything, because these are two musical jewels, just like La Giralda is a jewel of architecture.

On the other hand, there are the stale, obstinate purists, those who chastise anyone who doesn’t perform flamenco in the way they conceive and understand it. If, for example, these purists only like Antonio Mairena, they dismiss anything that’s not sanctioned by the dogmas established by this great master. They don’t understand that if flamenco is more than a musical genre and dance style, but rather a culture and a way of life, then it’s meant to evolve, because life evolves, just like music and dance does. It’s not possible to sing, dance and play the guitar today like it was done in the 19th century, because now life is different from what it was back then.

Flamenco wasn’t created in three days, but it took many years, even centuries, for it to take shape. Yet, it came to life in a specific historical period, the beginning of the 19th century, in a specific region, Andalusia, and it was created by people who lived a particular lifestyle. They were flamencos, Gypsy or not. They were lovers of dance, music and poetry. They were lovers of the night, of the traditions of their land, of their specific way of life and of their unique sensibility. However, two centuries later, anyone, anywhere in the world, is able to touch and move us performing flamenco.

Moreover, flamencos outside of Spain are more respectful of tradition than Spaniards or Andalusian themselves. Those who come to Andalusia from other countries to enjoy our art aren’t looking for commercial flamenco, but for authentic, traditional flamenco instead. They enjoy walking around Jerez and Triana to soak in flamenco history and also feel the cante of Fernando el de la Morena and watch El Salmonete singing with his elbow leaning on the bar of a tavern. That’s not old junk, that’s culture. And that, my friends, deserves respect, attention and care. There is no need to change it, as some would like to, in the name of modernity. Whoever wants to re-invent powder, can do so, but never to blow up the memory of the jondo, the pillars of an art that is not ancient or modern, but both.